The birth of a hurricane is a fascinating process, often starting from inconspicuous beginnings that evolve into powerful storms capable of wreaking havoc. Let’s delve into the early stages of hurricane development, where seemingly innocuous atmospheric disturbances transform into organized systems with the potential for destruction.

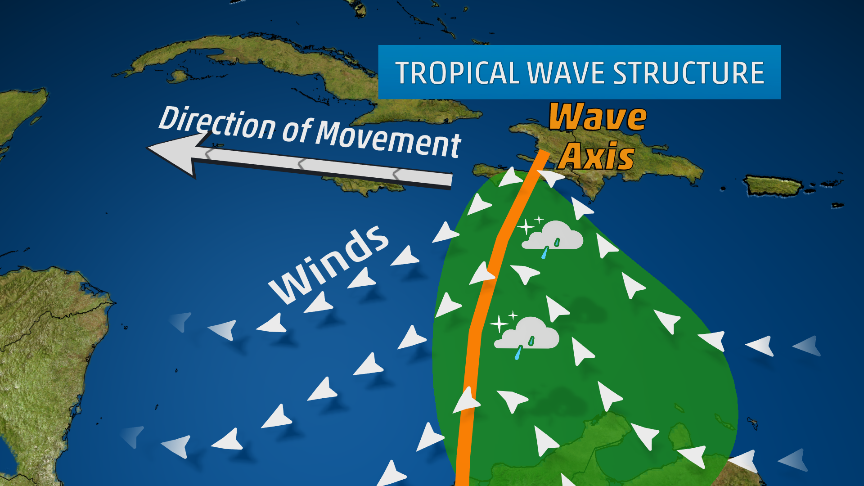

Tropical Wave: The Seed of a Storm

The journey often begins with a tropical wave, an elongated area of low pressure that originates over the warm waters of the tropics, often off the west coast of Africa. These waves, propelled by easterly trade winds, travel westward across the Atlantic Ocean, carrying showers and thunderstorms within their midst. While most tropical waves dissipate harmlessly, some possess the ingredients necessary to evolve into something more ominous.

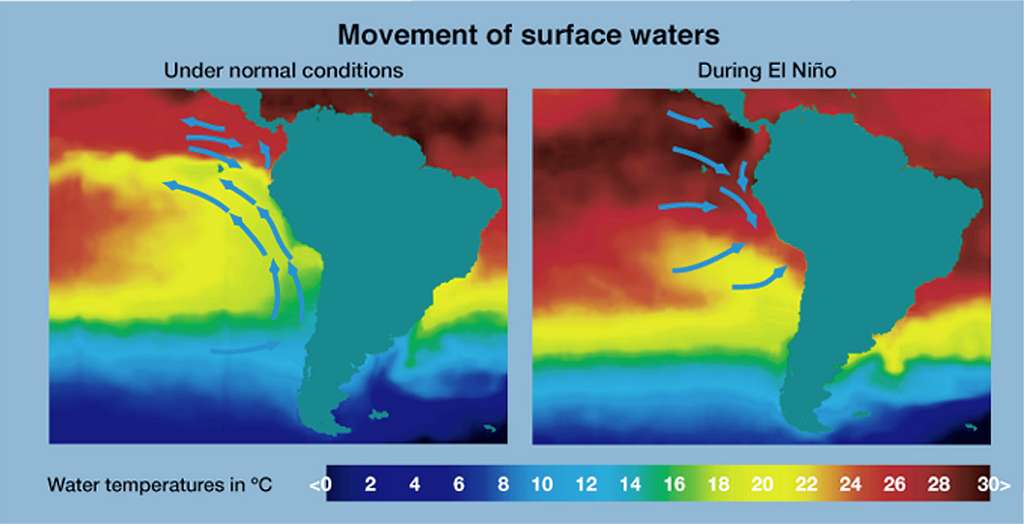

- Warm Ocean Waters: Hurricanes draw their energy from warm ocean waters, typically with surface temperatures of at least 80°F (26.5°C). This heat provides the fuel for the storm’s development and intensification.

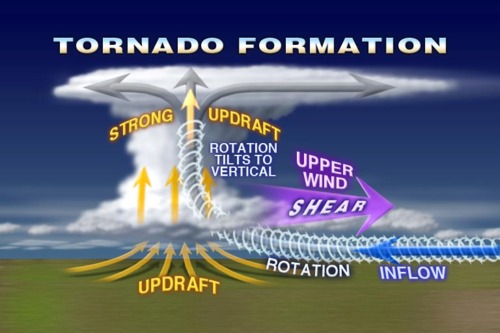

- Coriolis Effect: The Earth’s rotation creates a force known as the Coriolis effect, which causes winds to deflect to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. This deflection plays a crucial role in the cyclonic rotation of hurricanes.

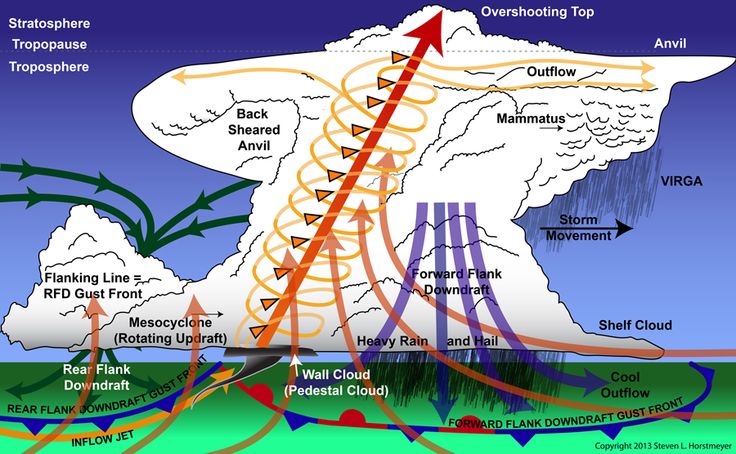

- Low Vertical Wind Shear: Vertical wind shear refers to the change in wind speed and direction with height. Low wind shear allows the storm to develop and maintain its vertical structure, while high wind shear can disrupt the storm’s organization.

- Pre-existing Disturbance: A pre-existing weather disturbance, such as a tropical wave or a cluster of thunderstorms, provides the initial seed for hurricane formation.

Evolution from Disturbance to Depression:

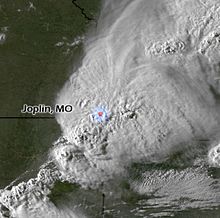

If a tropical wave encounters these favorable conditions, it can begin to organize and intensify. As thunderstorms cluster around the area of low pressure, a tropical disturbance forms. If the circulation becomes more defined and wind speeds reach up to 38 mph (62 kph), it is classified as a tropical depression.

The Critical Transition to Tropical Storm:

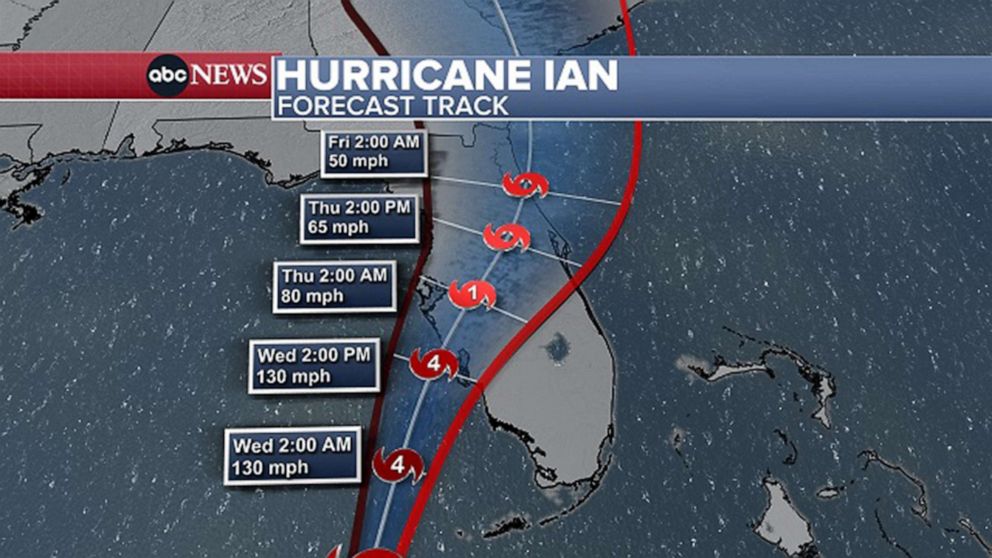

The transition from a tropical depression to a tropical storm marks a significant step in the storm’s development. As the wind speeds increase to 39-73 mph (63-118 kph), the storm becomes more organized and develops a distinct cyclonic circulation. At this stage, it receives a name and is officially recognized as a tropical storm, posing a potential threat to land areas within its path.

Stages of Hurricane Development:

- Tropical Disturbance: A cluster of thunderstorms with a weak circulation forms over warm ocean waters.

- Tropical Depression: The circulation becomes more organized, and wind speeds reach up to 38 mph (62 kph).

- Tropical Storm: Wind speeds increase to 39-73 mph (63-118 kph), and the storm receives a name.

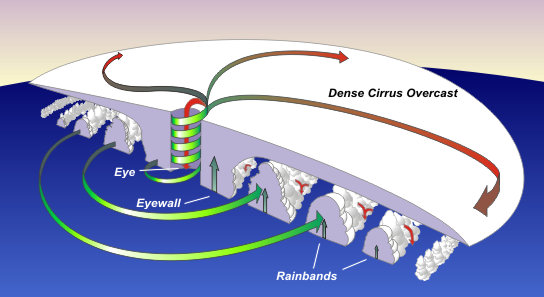

- Hurricane: Wind speeds reach 74 mph (119 kph) or higher, and the storm exhibits a well-defined eye surrounded by a ring of intense thunderstorms known as the eyewall.

Eye and Eyewall Dynamics:

The eye of the hurricane is a relatively calm area of low pressure surrounded by the eyewall, the region of highest winds and heaviest rainfall. Air rises rapidly in the eyewall, releasing latent heat and fueling the storm’s intensity. The eye forms as a result of the balance between the inward-flowing air and the upward-rising air in the eyewall.

Factors Influencing Intensity:

Several factors influence hurricane intensity, including:

- Sea surface temperatures: Warmer waters provide more energy for the storm to intensify.

- Ocean heat content: The depth of warm water also plays a role, as deeper warm layers provide more sustained energy for the hurricane.

- Atmospheric moisture: Higher moisture content in the atmosphere can fuel stronger thunderstorms and contribute to intensification.

- Upper-level atmospheric conditions: Favorable upper-level winds can help vent the storm and promote further intensification.

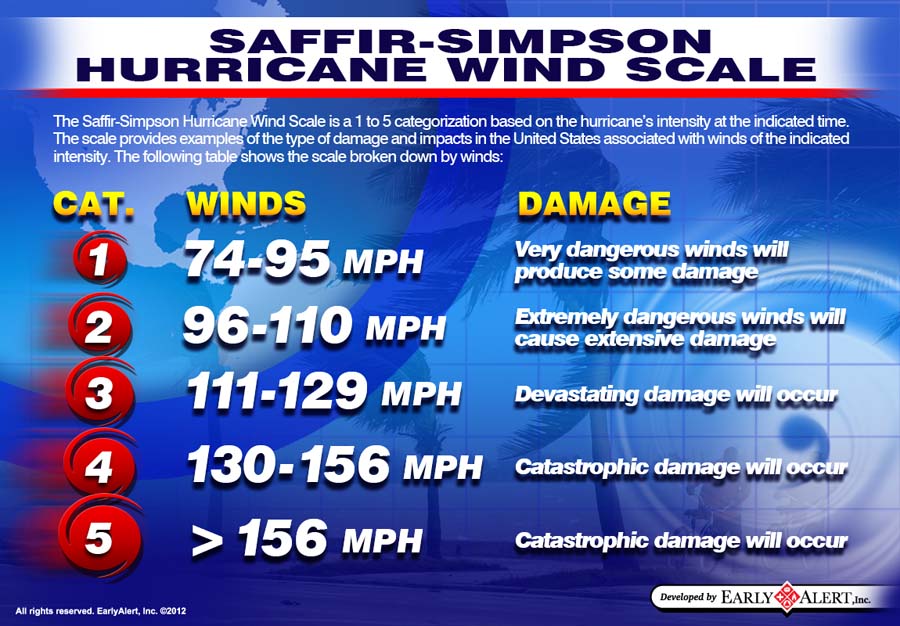

Understanding Hurricane Categories and Associated Damage

Hurricane categories, based on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, classify these storms based on their maximum sustained wind speeds and the potential damage they can inflict. This scale helps communicate the severity of a hurricane and guide preparedness efforts.

Category 1 (74-95 mph):

- Damage: Primarily to trees and foliage, with some damage to roofs, siding, and unanchored mobile homes. Power outages are likely.

- Historical Examples: Hurricane Gaston (2004), Hurricane Humberto (2019)

Category 2 (96-110 mph):

- Damage: Extensive damage to trees and foliage, with significant damage to roofs, siding, and mobile homes. Power outages can last for days or weeks.

- Historical Examples: Hurricane Frances (2004), Hurricane Zeta (2020)

Category 3 (111-129 mph):

- Damage: Devastating damage to trees and foliage, with major damage to roofs, siding, and mobile homes. Structural damage to small buildings is possible. Power and water outages can last for extended periods.

- Historical Examples: Hurricane Katrina (2005), Hurricane Irma (2017)

Category 4 (130-156 mph):

- Damage: Catastrophic damage to trees and foliage, with severe damage to well-built homes. Roofs can be completely torn off, and exterior walls can collapse. Power outages can last for weeks or even months. Extensive coastal flooding and inland flooding are expected.

- Historical Examples: Hurricane Harvey (2017), Hurricane Maria (2017)

Category 5 (157 mph or higher):

- Damage: The most catastrophic damage, with complete roof failure and wall collapse on many residential and industrial buildings. Most trees will be snapped or uprooted. Power outages can last for months, and areas may be uninhabitable for extended periods.

- Historical Examples: Hurricane Andrew (1992), Hurricane Michael (2018)